From the Bantu-Kongo, the Akan, Zulu, to the Twa, the traditions of African spiritual systems have existed for thousands of years dating back to the dawn of the earliest civilisations known to (wo)man. However, since the emergence of the Abrahamic faiths, namely Judaism, Christianity, and Islam from 100AD onwards, and the imperial conquests that followed, African spiritual systems have suffered a constant barrage of negative press, stigmatisation, and demonization to a significantly greater degree than their mainstream counterparts.

Too often have we heard negative associations made with “voodoo” or “juju” to witchcraft, or even all African spiritual practises being viewed as generally “evil” with practises being considered, for want of a better word, backward. Film director and educator Dalian Adofo, director of documentary Ancestral Voices: Esoteric African Knowledge, argues that African spirituality is often subjected to condemnation without investigation. That people are all too quick to dismiss African spirituality, without actually finding out what its fundamental precepts and principles are for themselves.

Of course, to speak of African spiritual systems as a homogenous entity is misleading and severely limiting. However there are fundamental principles found in each, such as collectivism, humanism and the reciprocal relationship between human beings and nature which connects them all.

The Bantu-Kongo are people of the Kongo kingdom. This was a prominent central African state during the medieval era with more than 60, 000 inhabitants of the capital city Mbanza Kongo alone. They believed that “God” is a balance of both feminine and masculine energy. As a reminder of this concept in the human form, the left side of the human body was named female, and the right side male. This concept of duality, of male/female, darkness/light, positive/negative, was believed to be the order upon which the universe was established and manifested through every living organism.

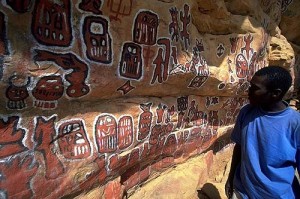

Dogon cave art, Mali, West Africa

Geographically, if we travel across to the Dogon people of West Africa – whose civilisation dates as far back as 3,000BC – we see the conceptualisation of this dual principle of balance or “twinness” in a different form. The Dogon believe that it was Amma, the divine creator of the universe, who ordained that all living things be manifestations of this universal principle.

The dual principle of balance dates as far back as the early civilisation of ancient Egypt. The epithet of Ma’at, a goddess that symbolised this, as well as harmony, truth, and order, is an example of how the world and the order of the universe was conceived in African spirituality, across both space and time.

One of the most widespread lies about African spirituality is the notion that they are polytheistic. That, in effect, those who observed African spiritual systems were worshipping multiple gods, and not the one true “God”, which – regardless of whether or not there is anything wrong with worshipping multiple gods – was not the case. In fact, thousands of years before the emergence of the Abrahamic faiths it was the Kemetic spiritual tradition of ancient Egypt that was the first to introduce the concept of monotheism, conceptualising the monotheistic principle of the one true “God” as “Aten” during the rule of Akhenaten (Amenhotep IV) in the 18th dynasty.

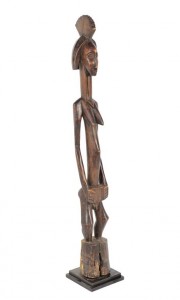

Another misconception, popular among cynics, is that statues are used as a form of idol worship.

Each religion or spiritual practise has their rituals for connecting to a higher divine source. For example, in Christianity, you have the crucifix, which is often worn around the necks of believers. In Islam prayer beads may be used to facilitate prayer. These symbolic tools are used to connect to a higher source. When they are revealed in mainstream society there is a general acceptance. However, if the same person pulled out the Orisha statue of Oshun, the Orisha of love, maternity and marriage, as practised by the Yoruba spiritual tradition, a negative reaction is all that can be expected because of prevalent stigmatisation and negative associations.

Ivory Coast, West African fertility statue

In many of the African spiritual traditions it is believed that there is one “God”. They are referred to as Nzambi’a Mpungu Tulendo in Kikongo, the central language of the Bantu-Kongo people, which is translates as the “everything in everything”. As “Amma”, among the Dogon people, or “Oludamare” among the Yoruba. There are also manifestations of “God”, the divine creator entity, in different elements of living organisms. These are seen as reflections of god, much like the ocean and a rain drop; the same substance with only a quantitative difference.

In Burkina Faso they have a saying that “50% of the people are Christian, the other 50% are Muslim, but 100% are African spiritualists (animists)”. This means that regardless of your religious beliefs, as an African, it is imperative to understand and pay homage to the beliefs and traditions that were held by those who came before you, the same traditions and beliefs that are being kept alive today.

No comments:

Post a Comment